With LME Week behind us and the first shots across the bow exchanged between miners and smelters for next year’s annual benchmark treatment and refining charges (‘TC/RCs’), it is possible that we may be heading for the first negative benchmark settlement in history. This has led many to question the viability of the current system, with expectations it could fracture along regional lines in 2026 as Japanese and European operators refuse to follow the lead of Jiangxi Copper and the China Smelter Purchasing Team’s (CSPT) agreed level with Antofagasta. It also begs the question, why on earth would any smelter group sign up to pay for the privilege of treating concentrates?

The answer lies in the by-product revenue streams from which smelters also derive revenues. While TC/RCs are usually the largest contributor, operators also earn from sulphuric acid sales and the cathode premium – an amount charged on top of the LME price for delivering metal at a particular location. And crucially they also receive ‘free metal’, so called because this is the difference between the percentage of contained metal a smelter pays the miner for and what they can actually recover through their processing operations. Free metal often refers to the copper recovered above the standard 96.5% that is typically payable to the miner. However for precious metals the equation is more complex and worth a quick technical review.

Traditionally, smelting processes across the globe were separated into two groups, being either flash (using Outotec or INCO methods) or bath smelters (using Ausmelt/Isamelt, Noranda, Mitsubishi or El Teniente furnaces). Of the 36 primary smelters outside China monitored by SAVANT, these each account for around 50% of global capacity.

Chart 1: SAVANT monitored copper smelters using the Mitsubishi Process

While there are some differences between the two, most notable being bath smelters’ greater ability to remove harmful impurities like arsenic, bismuth and antimony, in both processes valuable precious metals are dissolved in the copper before being separated at the electrorefining step to anode slimes. As a result of the similarity in recoveries, ‘standard’ commercial terms developed for copper concentrates containing gold, on a sliding scale from no payment for those concentrates with less than 1 g/t of the yellow metal, all the way to 98.25% for concentrates with gold at greater than 50 g/t. Similarly for silver, there was no payment for material with less than 30 g/t, rising to a payability of 95% for greater than 1,500 g/t.

But with the build out of the copper processing industry in China, aided by a centralised economic model that could also allocate significant research and development resources, a number of new processes were introduced. One of these, Shuikoushan Smelter Technology (referred to simply as ‘SKS’) was developed in the early 1990s by Hunan Nonferrous Metals, a subsidiary of China Minmetals. It utilised an enriched-oxygen, bottom-blown design in contrast to the top/side blown established technologies. This was not only more adaptable to a variety of raw material feeds, but also able to recover a greater proportion of precious metals due to their higher concentration in the anode slimes. Of course, to read the literature this is not apparently obvious – such commercially advantageous information is something to keep close to one’s chest for negotiations!

Fast forward to today and now with two decades of operating experience, Chinese smelters have been able to tweak their processes to maximise the benefit of the SKS technology. Indeed as Table 1 shows, together with the requirement for further treatment to recover the typically high copper concentration in slag, for several years operational experience was the only drawback when compared to other technologies:

Table 1: Comparison of copper smelting technologies

Technology | Example | Pros | Cons |

Ausmelt / Isamelt | Mount Isa Jinguang | Flexible to feed High production efficiency Simple to operate | Further treatment of slag required Short service life of lance |

Double Flash | Xiangguang Amman | High production with continuous operation Environmentally friendly | High CAPEX Cannot treat solid cooling materials |

Flash | Harjavalta Toyo | Low fuel consumption Long service life Good SO2 capture | High CAPEX High energy consumption |

Side Blowing | Fubang Heding | Low CAPEX and OPEX Long service life High copper recovery | Short history of operating experience |

SKS | Shuikoushan Humon | Low CAPEX High recovery of precious metals Low energy consumption Long service life | Further treatment of slag required Short history of operating experience |

And with gold prices now above $4,000/oz, SKS has come into its own due to the benefits of better precious metals recoveries. For example, an SKS smelter processing a copper concentrate with 4 g/t of gold and a recovery rate of 97% can expect to earn an additional $15/dwt (dry metric tonne) of concentrate treated. Or, to put it another way, that is the equivalent of $10/t in TC/RC terms. Quite good, but not enough to explain negative benchmark terms. Instead, the real prize looks to be in treating high silver concentrates. At a scarcely credible $80/oz today – and given a similar 3% advantage in recovery over payability for a 1,000 g/t concentrate – the value to the smelter operator soars to $77/dwt of concentrates, or around $50/t in TC/RC terms! As such it is no surprise that SAVANT monitoring shows that the Shandong Humon smelter, one of the first to employ SKS technology, is going gangbusters at present:

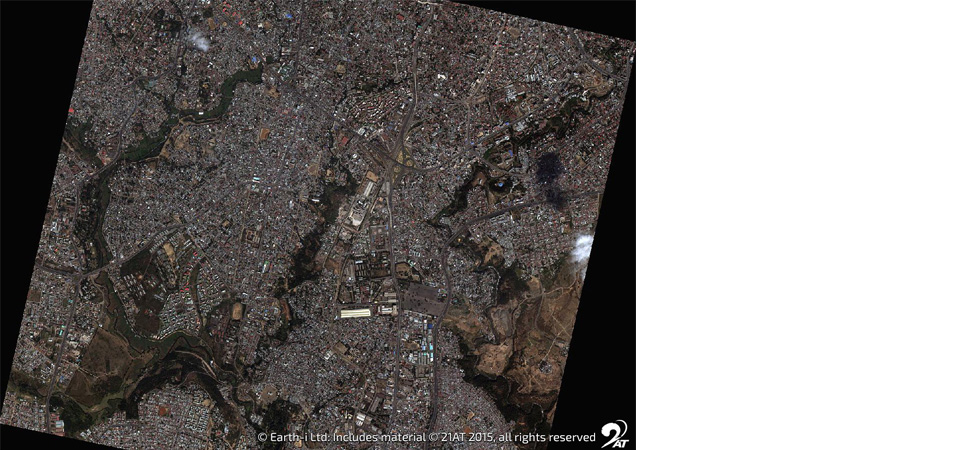

Chart 3: Shandong Humon I, January 2025 – Present

Yellow = active, blue = inactive, grey = no reading

And who owns the Humon smelter? That’s right – since 2019 it has been part of Jiangxi Copper’s portfolio of processing facilities, the same Jiangxi Copper who lead negotiations for the CSPT under the annual benchmark negotiations. Ahh … It’s all beginning to make sense!