Coffee is often sold as a ‘blend’, a mix of coffee beans from a number of sources, sometimes even from a number of different countries. Increasingly, however, many coffee drinkers have a preference for where their coffee comes from. They insist that they must have a cup of Kenyan, or Colombian coffee, possibly due to the perception of high-quality coffee from these regions, or certain ethical practices in the production. In practice, what this means is that the coffee is ‘single-origin’; coffee that is grown within the boundaries of one single known geographical area.

This area could be a country, or perhaps a single estate farm – on occasion it may even be implied that the coffee has been grown by an individual farmer. However precise the traceability advertised, consumer demand for single-origin coffee is considerable, and many large coffee chains now offer a single-origin choice as a result of this demand.

The region of origin of coffee beans is of huge importance to the resulting flavour of the coffee, for a number of reasons – whether a certain variety of coffee grown in that region, or as the result of local environmental or climate conditions, but whatever the reason, these regional differences exist. Coffee retailers often feature the source origin of their coffee prominently, taking advantage of consumer interest in origin to stimulate demand.

But how accurately can a coffee bean be traced back through the supply chain? Tracing origin back down to a single farm level is almost always impossible – certainly on the scales that large organisations in the coffee supply chain operate.

Smallholders coffee farmers in Kenya, for example, known for producing some of highest quality coffee beans, are generally organised into cooperatives; groups of farmers (often thousands of farmers) that join a cooperative society to pool resources, share knowledge, and benefit from management, agronomic, representative and commercial services provided by the cooperative. Many run the washing stations that process raw coffee, or contract with agribusinesses that provide these services. Coffee cherries brought by farmers to the washing stations are aggregated before the coffee beans inside are processed and sorted. Therefore tracing a single coffee bean back to one of these cooperative societies, or possibly one of the commercial estate farms in the country, is currently a more realistic aim than to an actual farm or farmer.

What is also possible, and perhaps more important than traceability at the farm level, is bringing transparency to the coffee supply chain, and through this, supporting sustainable farming practices and coffee that is grown under conditions where farmers are fairly rewarded for their contributions. Traceability demonstrates where the coffee came from; transparency reveals what exactly took place at each stage of the coffee supply chain.

Transparency is beneficial for farmers. ACCORD enables more advanced farmer profiles through mapping fields and gathering farm data. All of this taken together enables organisations at all stages of the coffee supply chain to predict the levels of production, and mitigate for any fluctuations if necessary ahead of time, helping ensure a consistent, high quality supply of coffee.

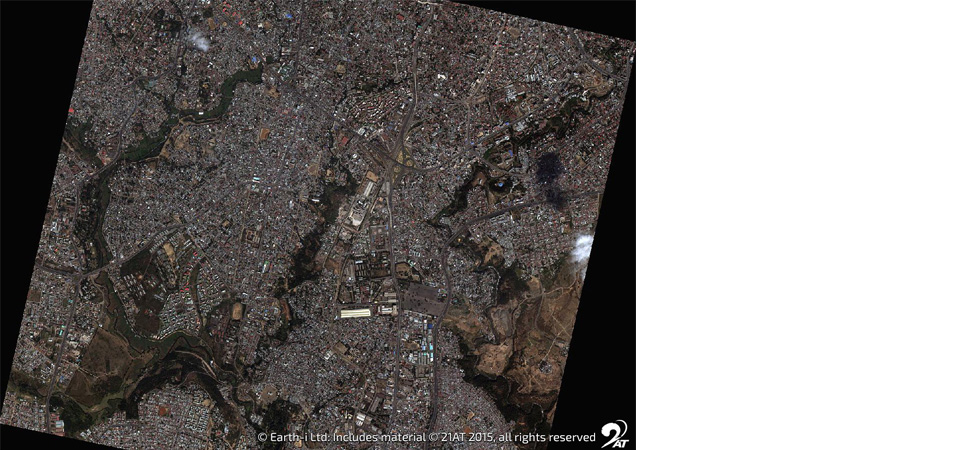

Furthermore, ACCORD provides an overview of a large coffee-growing area, monitoring crop health in each individual field throughout the growing season, identifying any risks to the coffee supply across a large number of fields, and targeting interventions to the fields that need it most before the impact of that risk becomes a major threat to productivity. This might mean, for example, identifying the conditions in which pests or disease can thrive before the damage of such pests or diseases has occurred. The data generated also enables coffee marketing companies and traders to estimate yields from their source farms and cooperatives more accurately, source coffee more efficiently, and sell coffee with greater confidence in sustainable supply. This broad view helps buyers and importers respond to the consumer demand for sustainability and transparency in their coffee purchasing habits, supporting the production and resilience of high-quality African Arabica coffee.

“I think we are on the verge of a quiet but important revolution in the production of cash crops by smallholder farmers across the world” said Jonathan Sumner, Business Development Director at Earth-i and on the ACCORD programme. “Agritech solutions, including the application of satellite data analytics, has been around for some time now, but largely focussed on larger-scale industrial farming and agribusinesses. With around 25-30% of our future food security dependent on smallholder farmers, its time we deployed new technology to enable these farmers to farm sustainably and beat climate change.”

Further, he added: “A consequence of this new technology is to enable big steps forward in supply chain transparency and traceability, making a stronger connection and shared interest between end-consumers and the farmers that grow their food. It’s a win-win.”

For now, consumers may demand that their coffee be grown in a certain location, but the sustainability and ethical concerns of these consumers might be better answered by revealing how their coffee was grown, rather than simply where.

To find out more, visit www.earthi.space/accord.

To download the new brochure, visit: content.earthi.space.

Earth Observation specialist brings over 25 years technology and applications experience to company offering daily high-resolution imaging and data…