It is often said that price forecasting is a fool’s errand when it comes to commodity markets – indeed many will remember a certain US investment bank’s call for $200/bbl oil back in 2008, before they were humiliatingly forced to revise this down to just $45/bbl within 6 months. But maybe the point here is that there is just too much information contained in price formation, so that instead it is better to focus on one side of the supply/demand equation, as Marian King Hubbert did successfully back in 1956 when he correctly predicted that oil production in the lower 48 states of the US would peak in the 1970s.

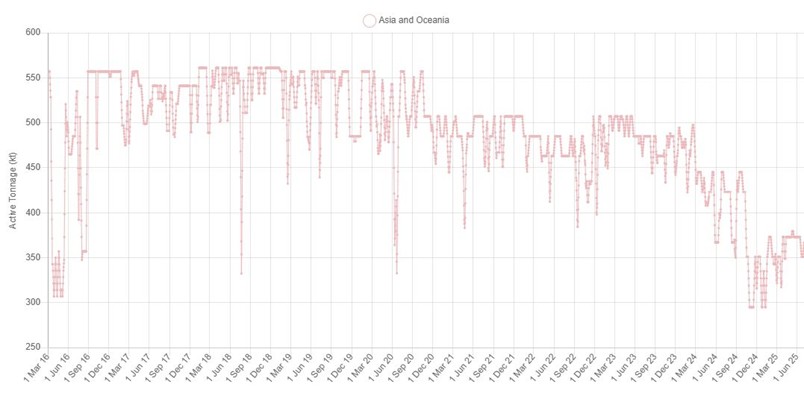

While it has become fashionable to focus on consumption following Alan Heap’s seminal 2005 paper that hypothesised ‘super cycles are demand driven’, the geographical availability of natural resources, and their economic extraction, is still the primary determinant of their usage. This month we look at some of the jurisdictions that increasingly find themselves on the wrong side of the nickel narrative, utilising the SAVANT platform’s latest feature tracking not just installed smelter capacity, but active capacity (Capacity * (1 – Inactive Capacity). Intuitively, this captures aggregate operating rates at a country and/or sector level, with some surprising findings.

Australia & New Caledonia

Chart 1: Asia & Oceania active nickel capacity, 2016 – Present

As the above chart shows, the deterioration of capacity utilisation in Asia and Oceania has accelerated in the last 18 months, in large part due to reduced activity in Australia and New Caledonia. Geoffrey Blainey’s ‘The Tyranny of Distance’ is a modern classic examining the former’s history in the context of its geographical remoteness, paradoxically concluding that this may have helped, rather than hindered, its economic development. This was certainly true of the country’s metals processing industry, where due to the vast distances involved from its roots with the Broken Hill Proprietary Company’s (BHP) mining of the eponymous massive sulphide orebody in the mid-1880s, smelting operations tended to near or co-locate with mining operations.

With this playbook well established, the Kambalda nickel boom of the 1960s in Western Australia saw the construction of the Kalgoorlie smelter, which began commissioning in 1972. In its heyday under the ownership of Western Mining Corporation (WMC) in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the smelter employed 400 people directly and produced over 100,000 tonnes of nickel-in-matte, the majority of which was then railed to the Kwinana refinery south of Perth to be turned into LME deliverable, class 1 nickel.

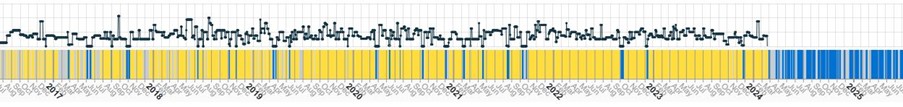

However, this is not a model well suited to 21st century supply chains where price is paramount. Labour in Australia is expensive compared to most jurisdictions, while its manufacturing sector lacks synergies and economy of scale, especially in competition with the behemoth nickel industrial parks built in Indonesia. So when technology improvements allowed the latter to convert from producing NPI to nickel sulphides suitable for the nickel-manganese-cobalt batteries needed for many electric vehicles, the writing was on the wall for BHP’s Nickel West operations, including the Kalgoorlie smelter. As SAVANT monitoring shows, October 2024 marked the end of over 50 years in operation.

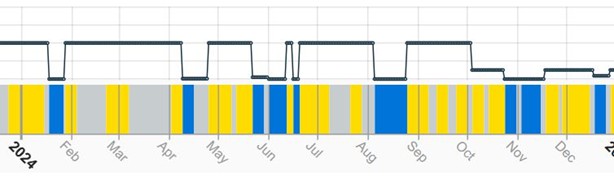

Chart 1: Kalgoorlie nickel smelter, January 2024 – Present

Yellow = active, blue = inactive, grey = no reading

While nickel has been synonymous with the economy of New Caledonia since its discovery by Jules Garnier in 1864, ‘the devil’s copper’ has also been a lightning rod for the local Kanak population, who for many years were only peripheral beneficiaries of the industry by comparison to French and other multinational companies. With wealth centered on the capital of Noumea, the indigenous people of the Northern Province were particularly aggrieved. That is why the closure of the 60 kT/a Koniambo plant last year is particularly galling – this was a project near Kone, 210 kms to the northwest of Noumea, that was meant to help redress regional inequality in the French overseas territory. As SAVANT monitoring shows, the $7.5 billion, 67-metre-tall furnaces now sit idle, while local businesses and restaurants that once supported a workforce of over a thousand people are mostly shuttered.

Chart 3: Koniambo ferronickel smelter, 2017 – 2024

Last year’s riots, the catalyst for which was an attempt to broaden voting rights beyond the ‘frozen electorate’ set out in the 1998 Noumea Accord, also had a significant impact on operations at Eramet subsidiary Societe Le Nickel’s troubled 56 kT/a Doniambo plant. Following a debt conversion (read forgiveness) agreement with the French government in March last year, the future of the loss-making site looked more promising, despite having to contend with high energy costs. However, that was before the civil unrest which has rumbled on into 2025 with the recent blockade of the Nepoui mining center. Eramet did not disclose the extent of lost production at Doniambo in its 2024 annual report, however as SAVANT monitoring shows, estimates of between 30-40% look to be quite accurate.

Chart 4: Doniambo ferronickel smelter, 2024

… even China …

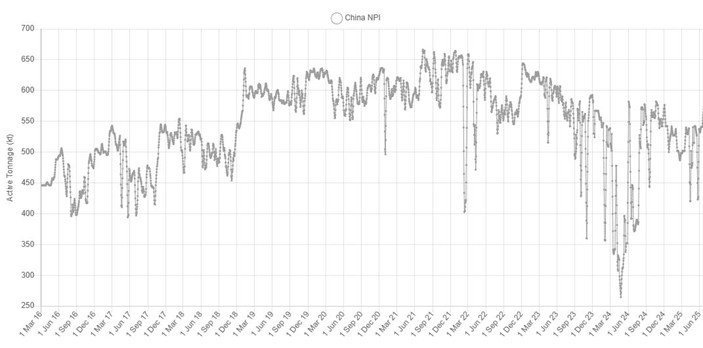

Although not as exposed as other jurisdictions, China has nevertheless started to feel the relative cost pressure from NPI in Indonesia, with onshore active capacity on a skittish downtrend since peaking in 2021. But with many of the new plants being built in the SE Asian archipelago under the ownership of Chinese companies and in particular the world’s largest stainless-steel producer, Tsingshan, this is less of a demise than a relocation.

Chart 6: China NPI active capacity, 2017 – 2024

… and now Indonesia?!

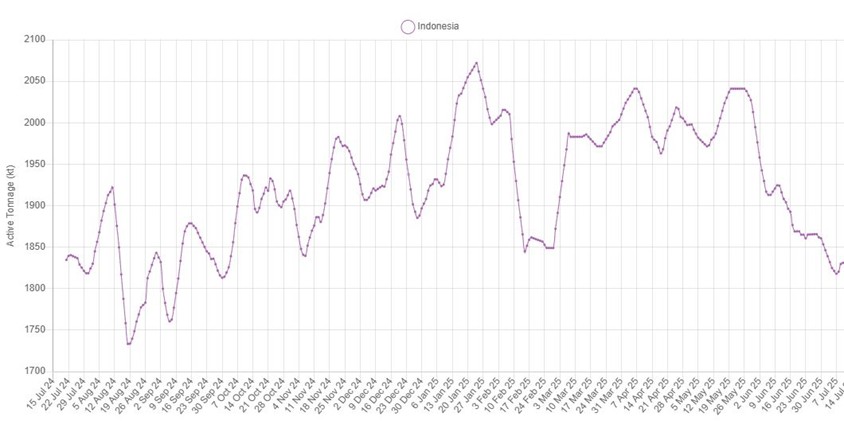

However this is not to say that the transition has been smooth, as Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry have found out with their collapse into bankruptcy that has left a question mark hanging over the future of the massive 192 kT/a PT Gunbuster facility in Morowali Utara, Central Sulawesi. For now, SAVANT monitoring shows that despite recent reports of delayed payments to local energy suppliers and a lack of funds to buy nickel ore feedstock the plant is still operating, albeit at much reduced capacity than its 24 installed RKEF lines would allow. A few years ago it would have been unthinkable that Indonesia could be on the wrong side of the nickel industry narrative, but together with the recent shuttering of Tsingshan’s GCNS and SMI joint venture smelters, the warning signs are certainly flashing as active capacity appears to have peaked.

Chart 6: Indonesia active capacity, 2017 – 2024

Central to Hubbert’s case was his observation that discoveries of oil had topped out in the 1930s, so that he anticipated production rates may also follow a similar bell-shaped curve after a time lag linked to the annual rate of extraction. With a recent report by climate consultancy Celios citing Indonesia’s nickel reserve life at just 11 years, together with our active capacity tracker, we have everything we need to calculate the year. We’ll go ahead and trademark SAVANT Peak Nickel Theory before the cybersquatters get hold of it.