While 2025 has been turbulent for markets and geopolitics alike, the challenge to the status quo has not been without warning signs. Against the backdrop of a number of geo-political rivalries for which the clock has been ticking for many years, flashpoints have turned to more prolonged, and potentially redefining, conflicts (the most dangerous of which may yet be to come as territory in the Western Pacific remains a bone of contention). Parallels to the metals’ processing industries are obvious with the reversal of globalization already reshaping the map for these industries, as nation-states embrace the philosophy of strategic sovereignty across key sectors of the economy, with critical minerals and metals to the fore.

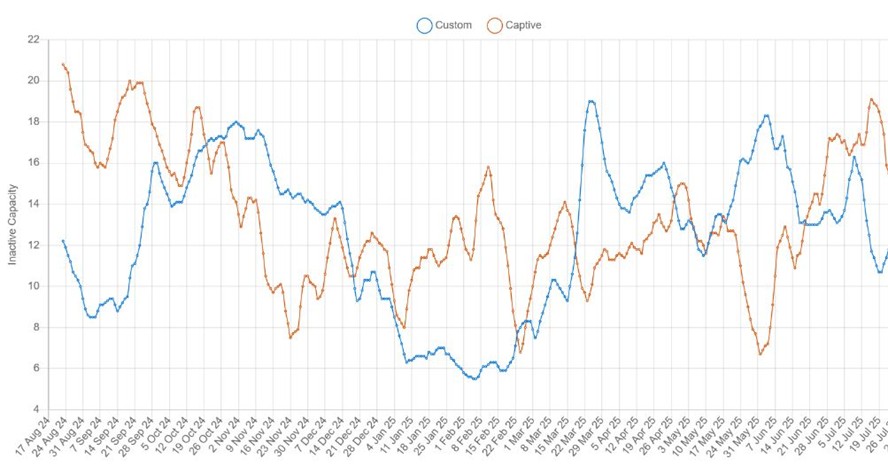

It is in this context that we turn to one of the most repeatable patterns identified by SAVANT since Earth-i first started measuring operational signatures of the world’s copper smelting industry from 1st March 2016 – namely the differing behaviours of custom and captive smelters at this time of year. Custom smelters, who rely on third parties for their feed, will run hard through the summer in order to have stocks of metal in advance of peak demand season with the resumption of economic activity in the northern hemisphere – and construction in particular – in the fall. Captive smelters on the other hand usually see a lull in activity as employees take their holidays, shifts reduce and operators take the opportunity to undertake maintenance programs. So far, as Chart 1 below shows, 2025 has gone exactly by the playbook.

Chart 1: Custom and captive smelter inactive capacity series, 2016 – Present

From here custom smelters then change tack and themselves start to take downtime so that their collective inactivity increases, giving the appearance of a loose market before negotiations for next year’s benchmark treatment and refining charges (‘TC/RCs’) in LME Week in October. So why do we think that 2025 might be the exception that proves the rule? The answer lies in the shift in the balance of power between miners and smelters.

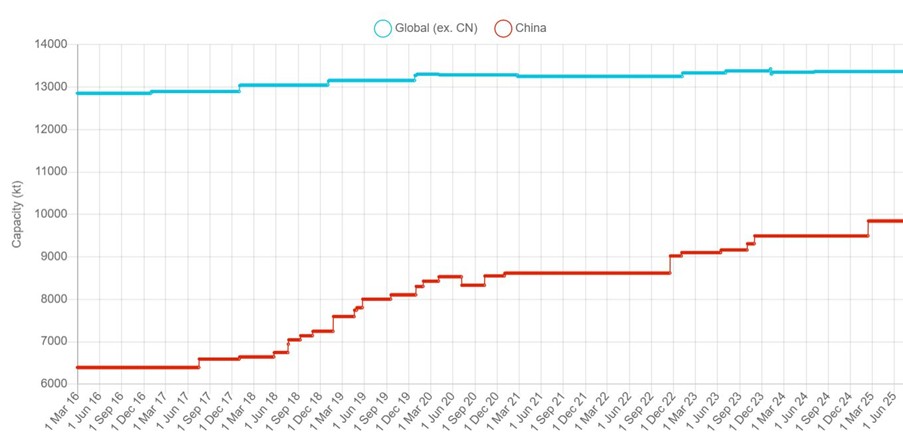

Since 2016 we have seen that over 87% of new smelting capacity globally has been added in China (see Chart 2), overwhelmingly as custom plants treating imported concentrates. The increase in the number of facilities in the east and south-east is testament to this, mirroring population and associated industrialization and urbanization trends. Together with the addition of new members, this should have conveyed greater negotiating heft to the China Smelter Purchasing Team (CSPT). Of course, this has not happened by lucky coincidence.

Chart 2: China and RoW smelting capacity, 2016 – Present

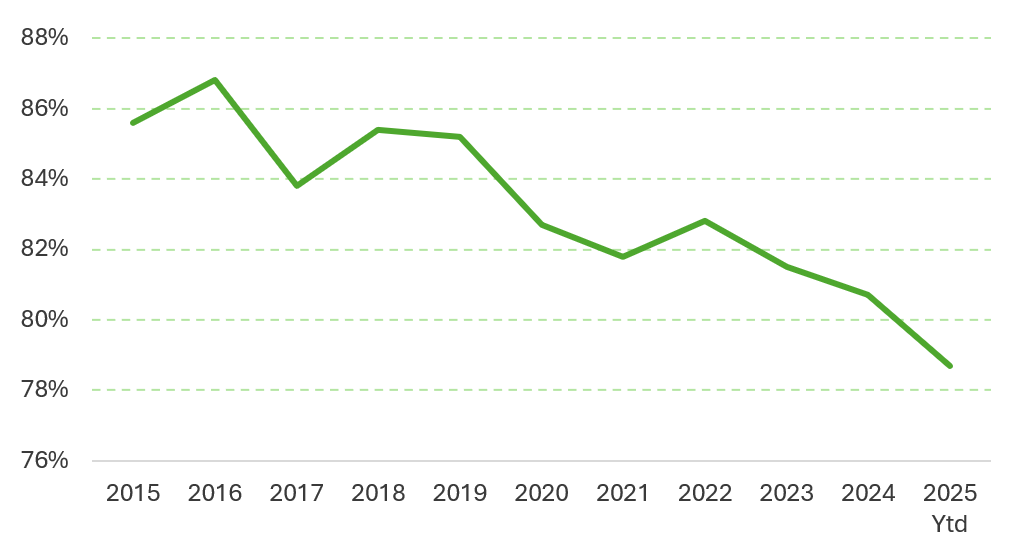

However, what was no doubt a deliberate strategy to extract better benchmark TC/RCs through greater collective bargaining power might be seen in hindsight to have been ‘too successful’. This is because at the same time, we can see in data from the International Copper Study Group (ICSG) that mine supply has struggled to keep pace with processing capacity, so that mine capacity utilisation has fallen from 86.8% in 2016 to just 78.7% in the first 5 months of 2025 (see Chart 3).

Chart 3: Mine Capacity Utilisation (%, ICSG data), 2016 – Present

As a result, while the CSPT’s influence has grown within the ranks of processors, the overall balance of power has shifted in favour of the miners. Furthermore, this has only been exacerbated in 2025 by the build out of new smelting capacity in Indonesia that will internalize concentrates onshore that were previously destined for the international market. And now there is a third arrow working against the CSPT – namely the growing concept of strategic sovereignty. Adani’s new 500 kT/a Kutch smelter is testament to the country’s attempt to reduce its reliance on imported cathode, while the potential construction of a new 400 kT/a plant at Ras Al Khair in Saudi Arabia is another example of the push for security of supply and self-sufficiency.

But maybe of most concern for the CSPT will be moves by governments to support/subsidise loss making operations that would otherwise shutter, helping to restore the balance of power between supply and demand. Following the Australian government’s bail out of Trafigura’s Hobart (zinc) and Port Pirie (lead) smelters, Glencore are lobbying the Queensland and Commonwealth governments to prevent the closure of the Mount Isa smelter, which they recently revealed is bleeding $30 million each month. This is a particularly vulnerable asset as Australia is a high-cost jurisdiction for both labour and electricity. Indeed, from the town’s birth as a mining center in the 1930s, its electricity system was self-contained due to remoteness, a drawback that remains to this day. As a result, and despite the Anaconda Copper Company being experts in the commercial production of electrolytic zinc, smelted metal (first zinc and lead, before transitioning to copper in the 1950s) has never been refined onsite, but instead railed 900 kms to Townsville for further processing. This is not a model well suited to the second decade of the 21st Century. Nonetheless, debate rages around the existential threat to an important regional center should the smelter be allowed to close.

Consequently, the CSPT remain locked in a battle that they probably anticipated would have swung their way by now. This has shone a light on the difference between strategy and tactics – with the former not delivering the favourable outcome they had planned, their smelters are now competing with capacity in other jurisdictions where their intrinsic cost advantage may have been negated. To ease back production now would be to blink, if not admit defeat. We think Beijing is unlikely to want to be labelled with a version of President Trump’s ‘TACO’ moniker, even if it does mean failing to extract better terms in negotiations than the record low benchmark TC/RCs for this year at $21.25/t. Consequently, we expect them to break with usual seasonal patterns and keep production and capacity utilisation high throughout this fall season.

The history of financial markets is littered with the bad bets of those who have been foolish enough to proclaim ‘this time is different’ … but never has price formation been so politicised. That’s why we believe this call straddles the fine line on the side of bravery.