Since the beginning of the 21st century China has achieved unprecedented gains in economic development. As Hugh Peyman notes in his excellent book ‘China’s Change: The Greatest Show on Earth’, the country doubled industrial output per person in just 12 years compared to the 154 and 53 years it took the UK and the USA respectively, both with populations that were around a hundred times smaller.

But the economic model of organising production around state owned enterprises (SOEs) has become outdated for a country now with weakening demographics, that no longer targets breakneck expansion to the goal of full employment. Beijing anticipated this back in 2015 with the release of the ‘Made in China 2025’ whitepaper that proposed to shift activity to Industry 4.0, encouraging greater adoption of high-tech manufacturing and digital technologies to maintain growth. Indeed, Premier Li Keqiang’s ‘China 2030’ report released in tandem hypothesised that the innovation essential to progress would not be delivered by government, which must instead reduce its role in production, but through private enterprise.

In releasing Adam Smith’s ‘animal spirits’, Beijing did however set a path to future turmoil in many industries, with nickel being a prime example. Nickel pig iron plants (NPI) were tacked on to the front end of stainless steel mills, as manufacturers adopted an ‘expand or die’ mentality. Meanwhile economies of scale conferred customers with ever increasing buying power, enabling them to negotiate price reductions. Declining profitability was then further exacerbated by cut-throat competition between players to secure orders and clear inventory overhangs as growth eventually plateaued. The resulting high turnover, low-margin economic state has been termed ‘involution’.

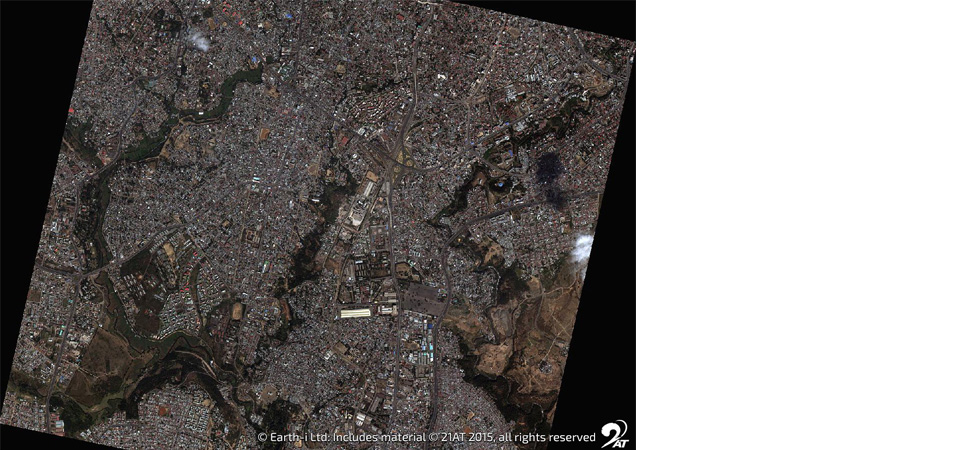

Chart 1: Nickel smelters in Northern China, September 15th 2025

Yellow = active, blue = inactive, red = closed

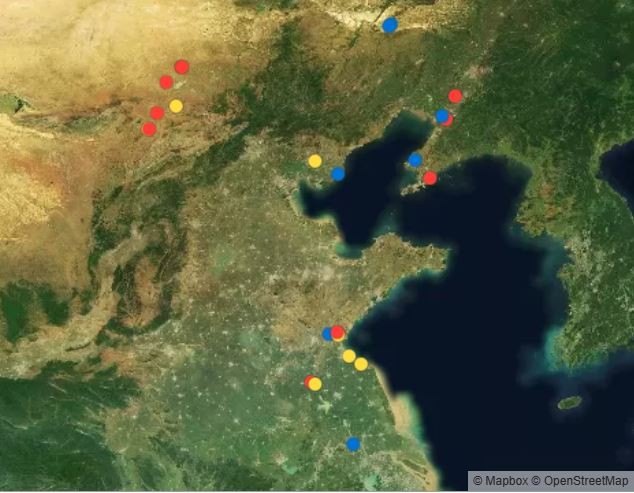

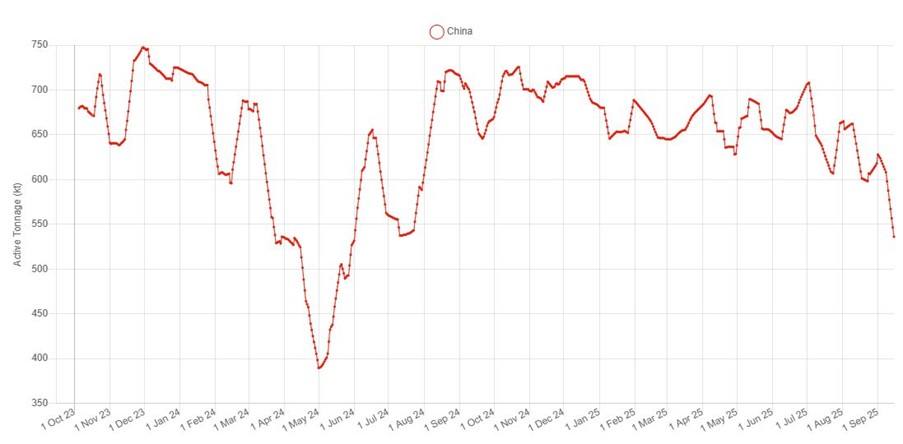

Fast forward to today and many of the plants that sprung up a decade ago have been forced to closed (see Chart 1). Of course the nickel industry onshore has also had its fair share of unique problems – not least of which stem from the ban of Indonesian ore exports back in 2014 – so that there has been a relocation of Chinese owned NPI capacity to the archipelago. But this cannot explain the recent sharp deterioration in active capacity of more than 20% since the middle of the year (see Chart 2). Nor can this be attributed to production disruptions at Shandong Xinhai’s behemoth 190 kt/a plant at Linyi, which was the primary reason for the previous dip seen in Q2 2024 (see Chart 3). Instead we attribute it to the central government’s broad-based ‘anti-involution’ campaign targeting excess capacity across processing industries, complimenting Beijing’s environmental goals, if not those of the planet as a whole.

Chart 2: China nickel active tonnage, October 2023 – Present

Chart 3: Shandong Xinhai NPI, 2024 – Present

Yellow = active, blue = inactive, grey = unknown

To take anti-involution to its logical conclusion, the Chinese government would create ‘national champions’ across industries, borrowing from a familiar playbook. But this time around Beijing seems cognizant that it must tolerate these being private companies (at least in some sectors and if their executives are not as vocal as Jack Marr).

Take GEM Co. Ltd for example, the Shenzhen listed battery materials producer that just reported a record H1 profit of ¥799 million (US$112 million). GEM promotes itself as ‘a global leader in waste recycling’ and while it may have a wide network of these plants, its second place in China’s list of the top environmental companies belies its production of nearly 44,000 t of nickel metal from laterite mining … in Indonesia. The following statement in the company’s financial report for the first half captures the triumphalism of combining profitability with an unabashed Nimbyist approach:

‘The Company’s nickel resource output steadily climbed and repeatedly hit new highs in July and August, achieving a great victory in the Company’s nickel resource history!’ (GEM H1 2025 Financial Report, p.12)

Nor should it be lost that across the GEM portfolio primary nickel extraction and processing is its highest margin business at 19%. And GEM is not alone in reporting stellar results – just last month Jiangxi Copper Company, China’s largest producer of refined metal, posted net income of ¥4.2 billion, it’s best performance since 2011. This would have been a good result under any circumstance, but in a year when other smelters are closing because of record low TC/RCs, it is nothing short of remarkable.

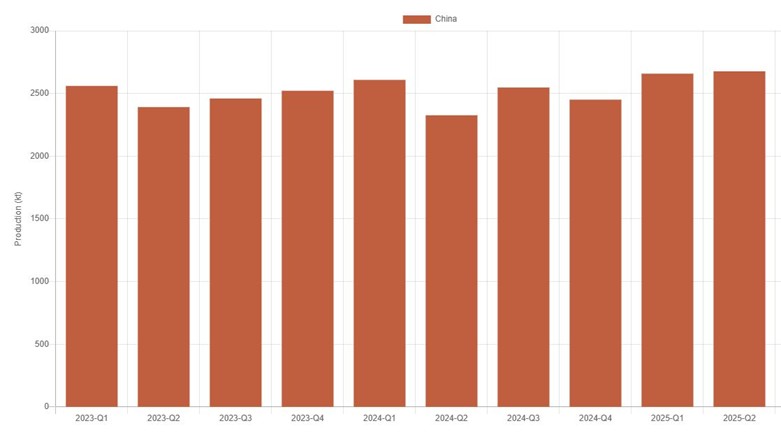

What will be interesting from here is if country level copper production can keep posting all-time highs – as evident from SAVANT’s copper production beta (see Chart 3) – to meet energy transition-fueled demand, despite the anti-involution drive. Beijing has already signaled that it will not allow the construction of ever more smelting capacity without owners having the concentrate upstream to fill it, as set out by MIIT’s 2025 – 2027 industry development plan issued back in February. This could be a powerful pincer move that both brings the concentrate market back into balance while simultaneously shoring up sector profitability.

Chart 4: Quarterly Copper Production, China, Q1 2023 – Present

But of course, those companies most likely to be able to fill future capacity are those with the financial resources to invest in developing mines, both domestically and overseas, like Jiangxi Copper, Zijin Mining, MMG or Chalco that all happen to be SOEs. As such GEM may yet be the exception that proves the rule with the future looking very much like the past, just more profitably … at least to start with.