The history of mining in Africa has not been an easy one. From colonial exploitation to the nationalisations of the 1960s and 70s, the continent has become synonymous with ‘the resource curse’ – the phenomena whereby those countries rich in mineral resources tend to have lower rates of development, democracy and standards of living. Even worse still, many communities have found themselves victims of ‘Dutch disease’ – overly reliant on a single source of income for their wellbeing and subsequently highly leveraged to the commodity cycle. However, it is possible that the electrification and decarbonisation imperatives of the 21st century present an opportunity – if not to right the wrongs of the past, then certainly to learn from them.

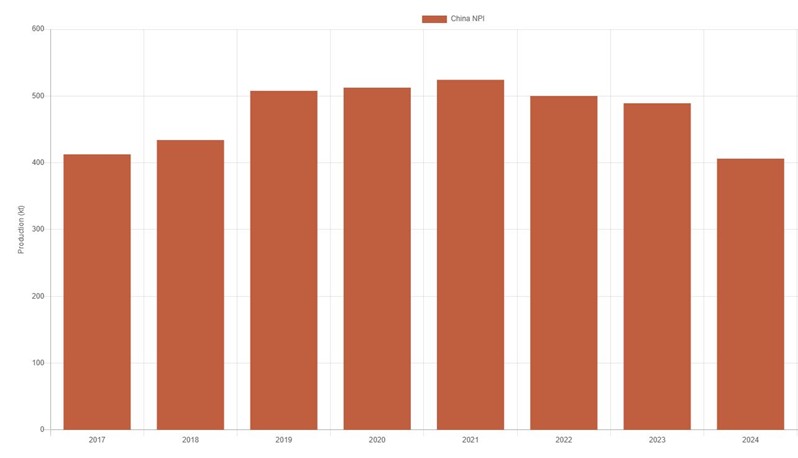

One such beneficiary could be the nickel industry in Botswana. In its heyday in the late 1990s, the country’s flagship Tati/Phoenix mine produced around 20,000 tonnes of nickel each year, equivalent to 2% of global production. Concentrates were then shipped to the smelter at Selebi-Phikwe, around eighty-five kilometers to the south, which also had its own integrated mine production. However, these operations could not survive the downturn that followed the ascent of the nickel pig iron industry in the 2010s, will all operations forced to close before the end of the decade.

Chart 1: SAVANT nickel production beta (kt), China NPI, 2017 – 2024

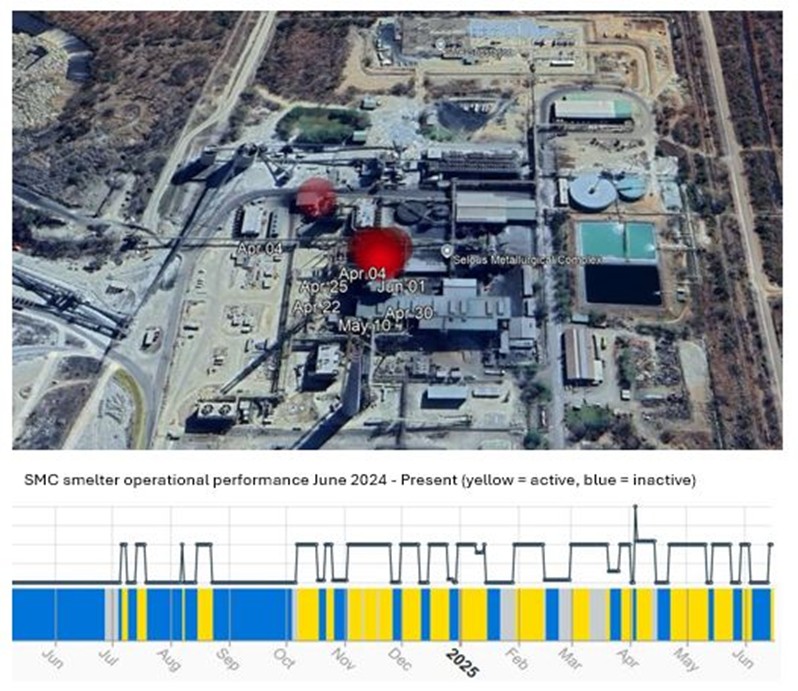

This may be about to change with both mines now under new ownership and with fresh capital, even if a refurbishment of the smelter looks beyond current ambition. But concentrates from here could supplement feedstock to the Selous Metallurgical Complex (SMC) in Zimbabwe, providing this site with a welcome source of third-party feed. Indeed, SMC is a good example of the resilience that is possible, having operated under Zimplats ownership since the beginning of the century and now undergoing a $544 million smelter expansion that will increase nickel processing capacity from 5 kT/a to 14 kT/a. In addition, the $190 million base metals refinery refurbishment will allow Zimplats to produce finished nickel, thereby reducing the need to ship matte to Impala in South Africa for finishing. It is no coincidence that SAVANT monitoring shows increasing activity at the site since October last year.

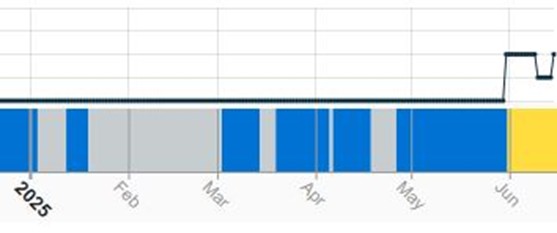

Chart 2: Thermal hotspot imaging for the Selous Metallurgical Complex, Q2 2025

Turning to copper, it will be interesting to see if new ownership at the Mufulira smelter could bring similar benefits. Following the $1.1 billion acquisition of a 51% stake in the plant and associated underground mine by UAE company International Resources Holding (IRH), in March last year, IRH detail that their investment ‘is being used to revitalize and modernise’ the site’s assets, with the goal being to produce 200,000 tonnes of cathodes within 3 years. However, this time SAVANT monitoring shows the steep learning curve that owners from outside the industry often face. Following a breakdown in the oxygen plant in December, initial reports suggested the smelter could be back online within a couple of months. But geospatial analytics shows this was most likely highly optimistic (or naïve?), with activity signals only detected since the beginning of June.

Chart 3: Savant inactivity profile, Mufulira, 2025

Blue = inactive, yellow = active, grey = no reading

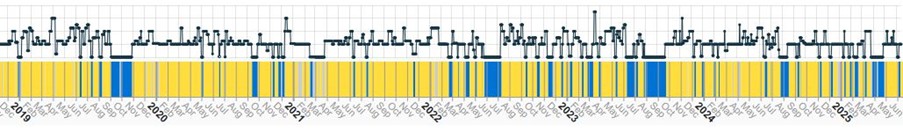

And as if the industry needed a warning from the ghosts of the past, recent events at Tsumeb in Namibia should sound a note of caution for today’s aspirants. Earlier this month owners Sinomine Resource Group (Sinomine) confirmed what users of the SAVANT platform have known for several months – namely that the eponymous smelter has been struggling for some time, manifesting in more frequent periods of inactivity. Indeed, the operating profile over the last nine years since SAVANT monitoring of the site (and 95% of industry capacity) began in early 2016 shows increasing periods of inactivity, never a good thing for a processing facility with high fixed costs.

Chart 4: Savant inactivity profile, Tsumeb, 2019 – Present

Blue = inactive, yellow = active, grey = no reading

Originally built to process copper and lead concentrates from the mine of the same name, the Tsumeb smelter has been operating as a stand-alone, ‘custom’ asset since 1997. Able to take concentrates with high levels of deleterious elements, the smelter developed a niche for itself in processing third party material under previous owners Dundee Precious Metals, as well as taking high arsenic concentrates from the company’s Chelopech gold and copper mine in Bulgaria. However now, with fewer ‘complex’ concentrates in the market amid a broader shortage of available material, Sinomine has said that it will pause operations for the time being. Needless to say, in a town of only ~35,000 people, losing around six hundred jobs will highly challenging for the community.

There is no doubt that Africa has a prominent role to play in the future of copper, and possibly nickel, production as well as a number of other elements crucial to the green energy transition. But maybe more so than in any other region, history tells us that victories will be hard won. Indeed recent seismic activity at Kamoa-Kakula that has resulted in severe flooding, with a knock-on effect to the commissioning of the smelter which is now not expected until October, serve as testament to this. We just hope future generations might reference the Mother Continent in the context of ‘copper redemption’ rather than the ‘resources curse’.